Special Hoagy Carmichael Q&A with Joe Lang (Part III)

Special Hoagy Carmichael Q&A with Joe Lang (Part III)

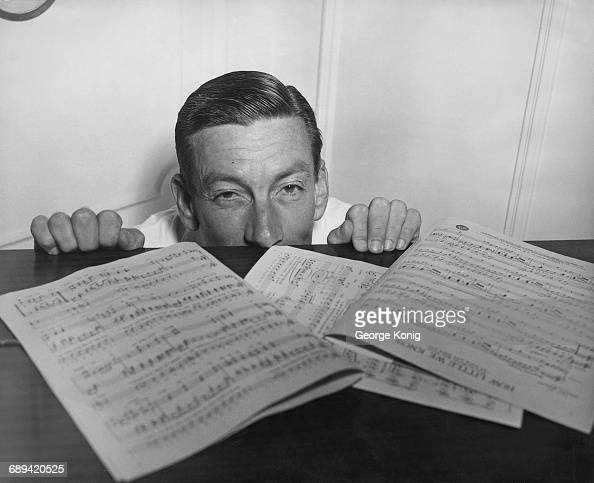

Happy belated birthday to the legendary composer Hoagy Carmichael, who if still alive, would’ve turned 123 this year on November 22nd!

In honor of the multitalented songwriter, we are wrapping up our chat with Joe Lang, who writes for the New Jersey Jazz Association.

JK: Tell us more about your interest in Hoagy Carmichael.

JL: He was my favorite songwriter. I became aware of him as a little kid because my dad used to sing around the house, and one of the songs he sang was “Stardust.” I was maybe four years old when I learned the words to “Stardust” and I used to go around and sing it to everyone and people thought what is this, a little kid singing about reverie?

Hoagy was the first person in the entertainment world I was aware of and over time he became a hero of mine. You know there’s an awful lot of great songwriters in American song—Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Ira Gershwin, Harlen Howard, and I love them all, but I love Hoagy more than anybody.

Somebody once asked me who my three favorite songwriters were and my answer kind of flustered a lot of people because I said Hoagy, Stephen Sondheim, and Thelonious Monk and they didn’t see the connection. But you know I’m not a musician I’m a fan, so I’m not technically able to talk about music but I’ve listened to enough that you pick a lot up. For me, though, music is a very emotional experience rather than a technical experience, so a lot of songs strike me a certain way. I always tell people my favorite female singer was June Christie, not because I think she was the best female singer but there was just something about her singing that struck me emotionally—the sound of her voice, the phrasing, the fact that she kind of sang flat some of the time, it was kind of intentional and just was the thing that I react to.

And of course, I love a lot of Hoagy’s songs and lyrics, and I sat next to Hoagy Carmichael at his 80th birthday tribute and that had to be one of the greatest thrills of my life—to meet Hoagy, well not only meet him, but there were several performers on the show that he was not familiar with that he was asking me about, so I was educating him in a way. And early in the show, I think it was the second song they played, Bob Crosby introduced one of the earliest songs that Hoagy wrote and recorded, and it was called “March of the Hoodlums,” and I knew Hoagy’s music well, but I just didn’t remember having heard that song. Then about halfway through the sang, Hoagy jabbed me in the ribs with his elbow and said, “You know I don’t remember a damn note of that thing—I’m not even sure I wrote it! And so, I go home, and I had an album with early Hoagy Carmichael material on it and sure enough that song was on it, and there was also a recoding of that same song by Duke Ellington, so it was not an unknown song in its day, although it’s not one of Hoagy’s songs that has continued on.

It was funny that one of the guys who was on the program at the birthday tribute was Dave Frishberg. Now I thought that Frishberg was a latter-day Carmichael but when Frishberg came out, Hoagy had no idea who he was. Now Frishberg is a wonderful songwriter—he has a lot of songs that are a little bit different; that don’t follow a formula, and Hoagy was the same way—I think that’s one of the things that appealed to me about him. It wasn’t like you’d hear a song by him, and you’d think oh that’s a Hoagy song. He wrote so many different styles of songs and all so well. And he continued writing into the fifties. He probably kept writing after.

JK: I’d like to switch gears a bit here to talk about your short review of Night Is Alive’s album My Ship.

You wrote that Willie Jones II is “among the premier drummers on the scene today and demonstrates on this album that he also shines as a leader who knows how to put together a superior band. You will dig sailing on My Ship.”

Now I am wondering—what is your favorite son on the album?

JL: You know I’d have to look at the album again because I review 10-12 albums a month and I listen to many more that I get in the mail all the time.

JK: There was “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “God Bless the Child,” “My Ship,” “Broadway,” “Taking a Chance on Love,” “Star Eyes,” “Wave,” “I Should Care” and “Christmas Time Is Here.”

JL: Hmmm but I would say the song “My Ship” was probably the one I liked best if I had to pick one.