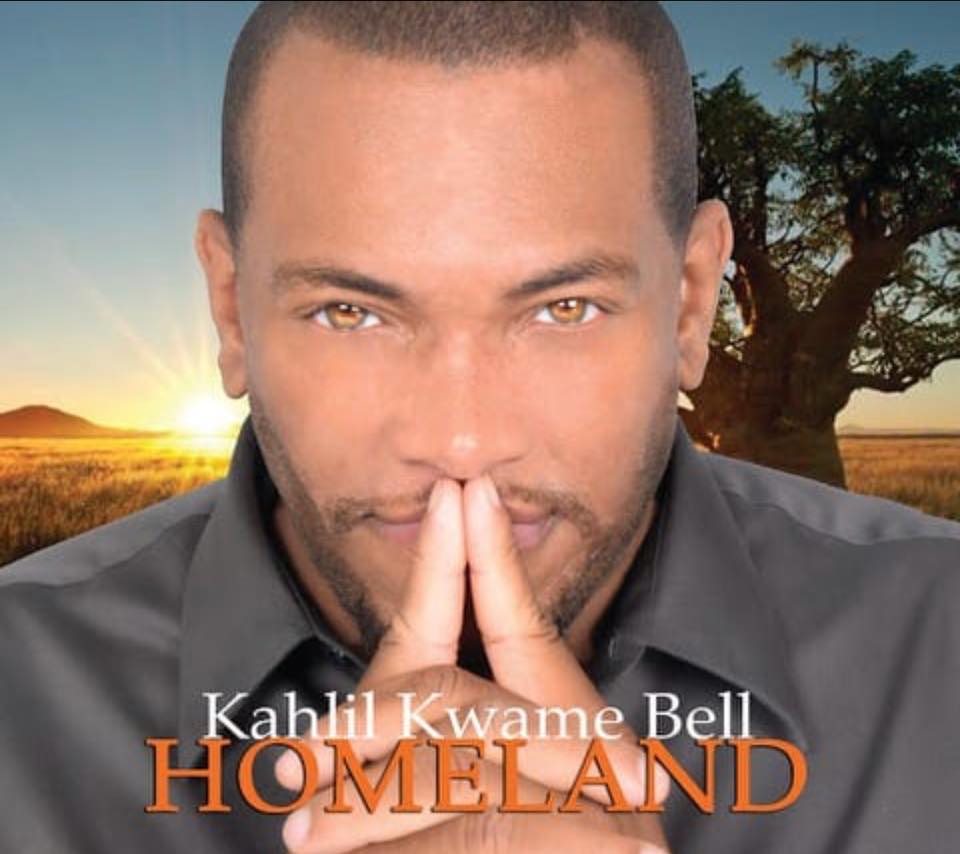

Feature Friday with Kahlil Kwame Bell

This Friday, we were lucky enough to chat with percussionist Kahlil Kwame Bell. Born in the Bronx in 1968, Kahlil Kwame Bell plays over 1,000 percussion instruments and explores a wide variety of genres, including jazz, rock, hip hop, classical and traditional African music. He has toured extensively with many famous artists, including vocalists Roberta Flack and Erykah Badu, and is passionate about reflecting the unity of cultures through music by layering sounds and instruments. His newest solo album is Homeland, which is an exciting journey through traditional African cultures and music!

JK: What do you love so much about physical CDs?

KKB: Most record labels that I know are still putting out physical CDs and I always ask for them, even if I have to pay for them, because I’m a person who still likes to read CDs and likes to connect myself with the record. I’m older, so I’m from the era of reading album covers, and I enjoy that, so I don’t like streaming and all this other crap. It disconnects people from artists, and, in my personal opinion, people don’t really know what it is a lot of times now to listen to a whole record and go on a journey from beginning to end.

I can name at least five records off the top of my head right now that I remember from beginning to end and I don’t know many people who can do that today, not even with hip-hop records, which are pretty popular. When I talk to my children, they don’t talk about albums anymore, they just talk about individual songs, and don’t get it twisted—I love individual songs—because that’s what exposes me to new art, but when I talk to young people, I’ll ask them who’s the artist and they’ll say, I heard them on this mixtape—they never really hear an album—they hear the artist through somebody else’s record.

JK: Which contemporary, mainstream artists do you appreciate?

KKB: I like Kendrick Lamar. I also go into this female rapped named Little Simz. She’s from England. She sings the Venom 2 theme track.

And my oldest daughter kept telling me about this girl H.E.R. and she showed me a song—I thought the girl could sing but musically, it was putting me to sleep. But then I did some research, I went on the internet, I checked her out and I realized how much of a prodigy she was, and I said oh no, she’s the truth. She plays instruments, she studied music her whole life, she’s dope. I heard her playing piano, playing guitar and I said, oh, she’s ridiculous, she’s the bomb. I can rock with her. So, now, I’m a fan of H.E.R.

JK: Tell me more about your interest in hip-hop.

I grew up in the Bronx when hip-hop first started, so I remember when hip-hop was at a very young age and President Reagan and other politicians were saying that it was a dying art form because it was kids in impoverished areas and no melody to it, just beats. I also remember not only white politicians saying that but black politicians saying that as well which is interesting because those were their children and grandchildren, but they didn’t dig it, which kind of reminded me of my grandmother’s era when people like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf were laying the foundation of American music with the blues.

When they were at their prime, the blues was the popular music of America, then all of a sudden, Chuck Berry comes playing the blues but playing it a little faster and dancing with it and making it into something that later became rock and roll. It’s interesting how when he came out with that, the older blues artists like Muddy didn’t dig it, but yet, people like Chuck Berry and Little Richard established rock and roll. They made blues in a faster tempo socially acceptable to the masses and made blues danceable versus what most people considered depressing when they first heard it.

So, I look at hip-hop in the same way. When hip-hop was first made it was a very conscious music, a very informative genre. You had people like Grandmaster Flast & The Furious Five, who brought the song “The Message,” which was a key, key, key song in hip-hop. Of course, the The Sugarhill Gang came out, and that is what made hip-hop socially acceptable. But it was “The Message” that gave people of America a look into the world of impoverished areas of cities because nobody really had an idea or a clue about that.

Hip-hop came out in 1979. The pioneer of hip-hop was Kool Herc. He was Jamaican, grew up in the Bronx. When he first started playing music in a certain kind of way, it hadn’t really been heard. At that time, the last 70s, early 80s, the Bronx had just started becoming predominately Puerto Rican. Prior to that, the Bronx had a lot of Jews, Irish and Italian. Hip-hop was the first genre where you saw Blacks and Hispanics creating together.

Hip-hop came out of the Reagan administration annihilating the performing arts programs in the public school system. From my grandmother’s generation to my mother’s generation, they can remember and tell you that they had music appreciation, they had band, which allowed a child to come out of the academic mindset into the creative mindset. When you’re dealing with the arts, it allows you to create something from nothing. It allows you to take a blank canvas and totally envision something in your mind, see where it’s going and create something beautiful, and unfortunately, sometimes academics doesn’t always do that—it’s right or wrong. If you write a sentence and it doesn’t include a noun, verb, and predicate, you messed up, so when it comes to these aspects of learning it can get very intimidating to a child, but when it comes to the arts, there’s this flexibility.

So, when, for some reason, probably for money, they killed that—no more arts, just academia in the inner city—the kids rebelled. All of a sudden you see graffiti and you see hip-hop growing. Not only did it grow but it became the language of the youth, and it became their story in existence. I grew up in hip-hop but the only reason I didn’t desire to be a rapper was because I played instruments, but in my time, most everybody wanted to be a rapper. It wasn’t making money, but it was stating your identity—I’m from Philly, I’m from Brooklyn, I’m from BK. Everybody had their little term that coined their own individual city, and that was the beauty. And we were children at that time and people are telling us it sounds like a bunch of noise, and perhaps it did, but it’s ironic that it started from that and look what it’s become today.

JK: Thank you very much for speaking with me today, Kahlil. I learned so much about the history of hip-hop! It was such a pleasure.

KKB: You’re welcome. I look forward to speaking to you again in the future!

This post was written by Blog Editor Jacqueline Knirnschild.